Causality - What makes things happen?

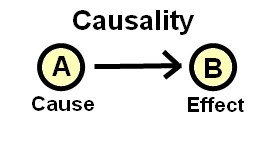

Causality

is often an important part of our understanding of how the world

works. It is a key aspect of our view of reality, and how

we go about predicting, or creating the future.

Those of you have already

read our article about Factors of Success know that hard work

alone is not a necessary and sufficient cause for success--here

is where we explain more about that.

We say

that A causes B, A is the cause, and B is the effect. These are two events that occur in time,

with A always preceding B, and with B seen as resulting from A.

Another way of putting it is, "If A, then B."

Humans recognize patterns, including those that happen and

repeat over time (temporal patterns).

So...why do we bring

this up???

For several reasons.

First of all, everyone, at one time or

another, looks for causes and effects. When we

try to figure out the whys and wherefores, were looking at

causes and effects. We do this to understand things that

happen, including things we want to happen.

People are

often concerned with cause and effect, when they set out to do

something. Their goal is the effect, and they seek to find

what causes, or actions on their part, will lead to the the

effect they seek (their goal).

And people often look to

understand the behavior of others, as well as why things happen

in the world at large. Humans are particularly adept at

this.

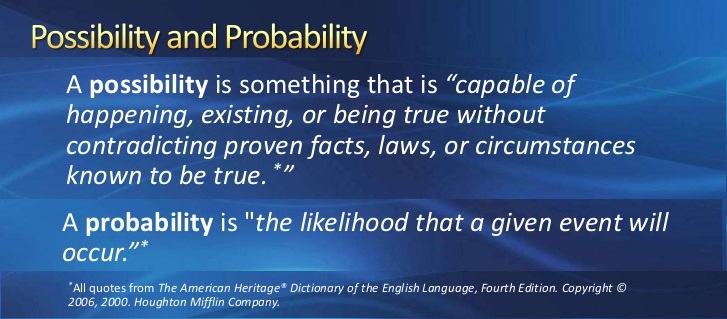

Possibility and Probability: In the process of examining

causes and effects, both possibility and probability are taken

into account. The latter is especially relevant in

correlational studies where multiple causes may contribute to

something happening.

Prediction and Quality of

Life: Scientists are particularly

concerned with this, as they try to figure out the causes and

events that occur in the world. If they do so correctly,

it can lead to predicting what will happen. AND...it can

lead to developing new technology that improves our quality of

life.

Second, when it comes to

reality, it can get complicated, so much so that folks don't

realize that it doesn't make sense to seek, or expect simple

causes for things. And that's because there are different

kinds of causes. These causes relate what is possible for

an effect to occur, as well as what sorts of causes can lead to

probable effect.

Third, and last, there is a

fallacy that often emerges, when people consider cause and

effect, one that leads them to making unrealistic decisions (see

below).

What

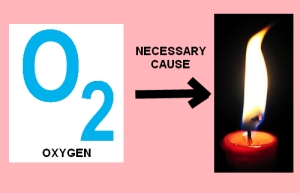

is a Necessary Cause?

Basically,

this means that A must be present for B to occur. If A is a

necessary cause of B, then the presence of B necessarily implies

the presence of A; however, the reverse is not true by default.

The presence of A alone does not imply that B will occur.

Another way of looking at it is in terms of possibility; a

necessary cause is one that makes something possible.

Oxygen must be

present for fire; however, the fact a room contains oxygen does

not automatically imply that there is also a fire in the room.

Oxygen is a necessary cause for fire. It makes it possible

to ignite something.

Oxygen must be

present for fire; however, the fact a room contains oxygen does

not automatically imply that there is also a fire in the room.

Oxygen is a necessary cause for fire. It makes it possible

to ignite something.

What is a

Sufficient Cause?

If A is a sufficient cause of B, then the presence of A

necessarily implies the presence of B. However, another

cause C may alternatively cause B. Thus the presence of B does

not imply the presence of A. A sufficient cause creates

the probability something can happen, but

Matches can be a

sufficient cause for igniting a fire, but so can others things,

like a short circuit, lightning, or a magnifying glass to focus

sunlight. So if there is a fire,

that does not necessarily mean there are also matches. The

level of probability can vary from one sufficient cause to

another (e.g., a lit match is a more probable cause for ignition

than a magnifying glass focusing sunlight, since the former is

more available and easier to use than the latter).

Matches can be a

sufficient cause for igniting a fire, but so can others things,

like a short circuit, lightning, or a magnifying glass to focus

sunlight. So if there is a fire,

that does not necessarily mean there are also matches. The

level of probability can vary from one sufficient cause to

another (e.g., a lit match is a more probable cause for ignition

than a magnifying glass focusing sunlight, since the former is

more available and easier to use than the latter).

What

is a Necessary AND Sufficient cause?

Now, as it

happens there are causes that are both necessary and sufficient,

in which case presence of cause A will always result in the

presence of effect B, and vice versa. In this case, we say

"B will occur if, and only if A occurs first."

These are

rare. Most causes are either necessary, or sufficient but

not both at the same time.

A gene

mutation associated with Tay-Sachs is both necessary and

sufficient for the development of the disease, since everyone

with the mutation will eventually develop Tay-Sachs and no one

without the mutation will ever have it

A gene

mutation associated with Tay-Sachs is both necessary and

sufficient for the development of the disease, since everyone

with the mutation will eventually develop Tay-Sachs and no one

without the mutation will ever have it

.

A Causal Fallacy

(one that occurs far too often):

This occurs most often when

folks don't know the difference between sufficient and necessary

causes and instead lump them together, which leads them to

concluding that...

...If a cause turns out to

NOT be sufficient, it must also NOT be necessary.

Now that you know the

difference between these two types of causes, you know this is

absolutely not true. But you can and will hear this sort

of fallacy stated concerning all sorts of things.

"Studies show

that simply spending money will not improve test scores in

schools. So we should be looking at something else, like

better teachers, or higher levels or parental involvement."

"Studies show

that simply spending money will not improve test scores in

schools. So we should be looking at something else, like

better teachers, or higher levels or parental involvement."

We should note that the the

conclusions are often implicit (that is, unstated). If

spelled out, the conclusion is that we should stop doing one

thing and start doing something else. And while doing

additional things may be beneficial, that does not mean we have

to stop what was already being done.

But this misses the point.

In the example above, the problem may not be just spending

money, but what the situation is prior to spending money.

In other words, if not much money is being spent at all,

spending more might be beneficial. But if a lot is being

spent, then it may be a matter of what the money is spent

on--there may be areas that won't benefit from further spending,

but areas where increased spending will be beneficial. It

does not follow that since scores haven't improved after

spending money, we should stop spending money and do something

else.

By the way and while we're

at it, this question about spending money is OFTEN missed

whenever people talk about government spending. Simply

looking at the amount being spent alone and then deciding that

more, or less needs to be spent based on the amount and the

current results is inappropriate. Further critical

thinking (discussed elsewhere on this web site) is called for.

At the very least, the amount being spent and on what should be

addressed prior to making any decision about further increases,

or decreases in spending.

By the way and while we're

at it, this question about spending money is OFTEN missed

whenever people talk about government spending. Simply

looking at the amount being spent alone and then deciding that

more, or less needs to be spent based on the amount and the

current results is inappropriate. Further critical

thinking (discussed elsewhere on this web site) is called for.

At the very least, the amount being spent and on what should be

addressed prior to making any decision about further increases,

or decreases in spending.

Logic vs. Science

It might interest you to know

that there are those, usually logicians, who will tell you that

Necessary Causes and Sufficient Causes, aren't really causes.

For them, ONLY causes that are both Necessary AND Sufficient are really

causes. They prefer to call the others "Necessary

Conditions" and "Sufficient Conditions." It's their way of

saying that they are "conditional" causes, because they don't,

in themselves always explain what causes something to happen.

But this is mostly a matter of

semantics, one that scientists ignore, because they know and

routinely deal with the fact that there are multiple causes, and

thus do not look ONLY for Necessary AND Sufficient Causes.

In real life, causes can turn out to be rather complicated,

for example, looking something like this:

Fortunately for us all,

researchers have a whole bag of resources to deal with all this,

including data collection methods, and data analysis models.

To

read our article about the factors leading to (i.e., causing) success

To

read our article about the factors leading to (i.e., causing) success

To

return to the Articles Page

To

return to the Articles Page